|

When I write about “witness,” I want to be clear about its broader meaning. Some will assume that because I am a Christian, hold ordination, and am from the south, that I am talking about “witnessin’ for the Lord,” or something to that effect. If you’re headed down that road, please, slow your roll. We can stand witness to a number of things besides the Creator, not the least of which might be one another.

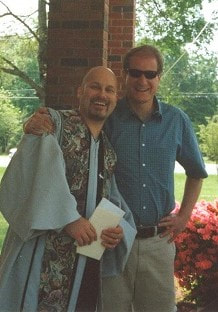

Thirty-two years is a long time to stand witness. In an earlier post, I mentioned my own conceptualization of family. I have a de facto brother, Ken. Once upon a time, on a pungent chemotherapy ward (as they were known then), one of my nurses walked into my room and asked if I would talk to the 17-year-old down the hall. He had, she said, the same type of cancer I did. That evening kicked off something more than friendship. A brotherhood was formed, based on shared experience, and try as I might, I haven’t been able to shake the guy for three decades. Actually, I’m glad. He’s been a witness to many of the life-altering events of my journey. We have been closer, as one might imagine, than many biological brothers. His favorite pastime is to annoy me with his adolescent texts and phone calls, but I love the big Neanderthal. There is a saying, “Don’t just do something—stand there!” Witnessing sometimes means just being a caring presence. Ken stood witness to my battle with cancer, particularly its aftermath. He watched the emotional and psychological toll it took on me. He witnessed my divorce and its recovery, and the powerful and meaningful existence I carved out with canines as a means of both theology and personal philosophy. He witnessed the metanoia (change of heart, as in “Change your hearts and lives, and believe in the good news!” from Mark 1:15, CEB) that I underwent as I responded to God’s call to seminary and professional ministry. Twenty-one years after our struggle together in the trenches of cancer treatment, Ken was called to witness another medical challenge when he took precious time to travel to the North Carolina Mountains after I had a heart attack on a cold day in Asheville, where we lived. In more recent years, as my health would deteriorate, the phone would ring at the times when I was contemplating the meaning of a life of pain or, more importantly, whenever it was time for the Carolina Tar Heels to beat the hell out of the Duke Blue Devils (as happened recently). When a major life decision or change is on the horizon, Ken calls. I mean, the guy has a sixth sense. His witness has meant a great deal for a long time. Are you called to witness? Consider the upshot of giving testimony to the life of another. Think of the potential in good will, life-long relationship, memories, and harassing phone calls you may be in for. That’s the good stuff. For whom are you called to witness? How will the act of witnessing help you help someone else? Give it a shot. The experience will probably change your lives for the better.

2 Comments

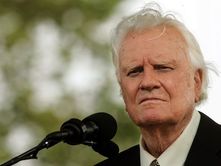

The Rev. Billy Graham, courtesy Mario Tama, Getty Images

The Rev. Billy Graham was a native Charlottean. That is one of the things we had in common. Like Rev. Graham, I was called to the ministry, and we shared a love for the North Carolina Mountains. He will be missed by many, especially in the South. Rev. Graham (“Billy”) was instrumental in my return to the church as an adult. His simple message of “God loves you and He has a plan for you” resonated with me. It was a message I needed to hear at the right time, for the right reasons. If he moved beyond that message, however, as he had in earlier years, that’s when I cringed and retreated. I’ve never been one for compulsory faith. The “You must make a decision!” theology can be a dangerous one. Consistently, conservatives could never get enough of Billy, and liberals had little, if any, empathy. When Billy and President Kennedy met, it must have been one interesting conversation! When he was young, Billy was not a fan of Catholics (or Jews, for that matter) and he made his views known. Later, Billy came to see people of other traditions and faiths as trying to do what most of us try to do—to live in concert with the God of our understanding. His message, generally, became more about God’s grace than human transgression. He was resolute in his stance that the ultimate path to God was through Jesus only, but his willingness to reach out to persons of other faiths increased with age, something a lot of Christians could learn from. Though worlds apart in our respective theologies and social philosophies (I don’t believe that my gay brothers and sisters are sinful by virtue of following their hearts, for example), Billy and I were probably more alike than different. Regarding the pureness of his heart, I have no doubt. I thought Billy’s address to the nation at the National Cathedral the Friday following the September 11, 2001 attacks was hopeful and relevant. Billy’s resolution to live a modest life as he comprehended it was admirable. I remember reading in his autobiography that although the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association was doing well, he refused the adoption of an airplane on moral grounds. He didn’t think it was right for the ministry to spend money on something like that, which is more than can be said for some of the televangelists of today. The Rev. Billy Graham grew up about 10 miles away from where I did. He was ordained to the Gospel Ministry, as was I. He had a great love for the Blue Ridge Mountains, as do I. He was conservative in his theological and social stance, whereas I fall in that grey area of “moderate” that irritates so many from the extreme ends of the liberal and conservative spectrum. More important than all of that, though, is that he was Billy. Like him or not, you knew where he stood. He was a true and faithful rider of the horse that rode hard for the Jesus of Billy’s understanding. He had an enormous impact, preaching to as many or more people than the apostle Paul, and for that alone, he deserves our respect. Thank you, Billy, for your service. With "Aslan," on a training day in Charlotte, early 1990's

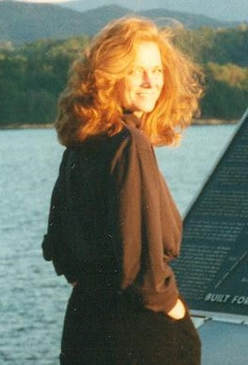

In an earlier reflection, I mentioned that dogs changed my life. I landed a job training dogs during a difficult transition. The relationships that were formed, the bonds created, the love of a human for another species—these were the things of dreams. Our own companions have seen me through a lot. The dogs that Penny and I have shared space with over the years have listened to my complaints, my plans, my sermons, my articles, my stories, and my fears. They helped me cope with intense clinical training, seminary papers and exams, the deaths of my parents, and job loss. They supported me through two heart attacks, a lung tumor and its surgery, the deaths of patients and friends, multiple relocations, and a host of other stress-inducing elements of life that are common to us all. When I first began training dogs, it was a hobby. Later, it turned into a vocation. As time passed, I realized that these creatures communicated with me in ways that defy adequate explanation. It is a spiritual connection; a sacred partnership based on trust. I was called to companion with these beings at just the right time, for just the right reasons. They believed in me, and I in them. Yes, even the protection dogs that were trained to “hit” my arm in its protective sleeve were often discriminating enough to still be my buddy. As the emotional and spiritual bond deepened, I began to share my experiences with others who understood exactly what I was saying. By the time I reached my final year in seminary, I was prepared to express this in a formal way, which I did in my master’s thesis/project, a research-based effort based on exploring the human-animal bond. How and with whom we commune says a lot about us. I’m proud to contemplate with my four-legged relatives. Mahatma Gandhi is credited with having said, “The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.” In an upcoming book, Called Yet Again, I discuss the aspects of my kinship with the canine through the lens of Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience. Within the context of reason and experience, I propose that the domestic dog is a participating member of the family system, and that the dog is capable of enough reason to define itself to others by virtue of its own emotional intelligence. In addition, the “Gih’li,” as the dog is known in Cherokee life and thought, has never once lied to me or tried to manipulate me into believing that I’m less than I am. The animals, especially the dogs, have given me far more than I’ve given them. They are more like us than different, and communing with them has been one of the great privileges of my life. Are you called to companion with nature in some way? I would love to hear about it. A servant’s heart is what it was. Yes. The cerulean-blue eyes and the flowing orange hair (reminding me to this day of a liquescent sunset over a Carolina beach) didn’t hurt, either. The heart of a true servant of the Great Spirit, though … that is what called me to commune with the woman that I’m honored to endure much of life’s trials and, certainly, its celebrations with. Chapel of Christ the King, an Episcopal mission in inner-city Charlotte, N.C., was a place where Penelope (Penny) felt at home. It was, in fact, a home away from home for her; a place to commune. When we met, she was volunteering her time there, working with the children at the preschool each week on her day off. She loved it, and it showed. The Right Reverend Gary Gloster, retired Bishop Suffragan of North Carolina, was the priest at the chapel at the time, and served as her spiritual advisor for a number of years, and was quick to point out the value he placed on her ministry there. Penny held membership at a rather well-to-do upscale parish not far from where she lived. It was always interesting to observe her demeanor and spiritual reflection after some time there or at the chapel. The juxtaposition was remarkable. Her ministry at the chapel caused her to come alive in a way like no other. It has been gratifying to observe her servant ministries in the church. Early in our relationship, she was also a co-mentor in the Episcopal Church’s Education for Ministry (EFM) program. It is an in-depth course (spanning four years) of theological education for lay persons. It was exciting to watch her help others gain forward movement in their own journeys. Later, when I was a clergy associate at Charlotte’s St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, she took another leadership position, this time on my youth team, where an extraordinary group of men and women helped me lead the ministry that consisted of the Montessori-based Catechesis of the Good Shepherd program, where she served as a catechist for the children. When we moved to the North Carolina Mountains, she was called yet again, this time to leadership as a sole mentor for another EFM group. Here in the Pacific Northwest, she is engaged once more, and I am excited to see what she does next. It continues to be an education for my own ministry to watch, listen to, and attempt to honor the woman with whom I’ve been fortunate enough to commune. It took me a while to get it right, to recognize excellence when it comes my way. When I saw it, embracing it was by far the smartest thing I’ve ever done. I dated many women who were exceptional in their own way. This woman, however, opened a window into my soul, and in blew the breeze of charity and agape, preceding the eros form of love that invariably followed. In the Letter of Paul to the Ephesians, the idea of mutual respect, sharing a high regard for God in Christ, is expressed: “and submit to each other out of respect for Christ” (5:21; CEB). Mutual respect is essential when considering a calling to commune with someone else. My call to commune with Penny came about at a time when I finally stopped working so hard to make a relationship happen. It wasn’t up to me. We were called to commune within the context of something greater than ourselves, and my life has been blessed beyond calculation. With whom are you called to commune? I hope you are as fortunate as I have been. Despite the many joys that life brings, most of us are pressured to endure something unpleasant during our lifetime. Sometimes it’s our own doing; other times it isn’t.

In the Book of Job, the main character (Job) is a person of great integrity, and yet he seems resigned to the misery that befalls him: “Surely humans are born to distress, just as sparks rise up” (Job 5:7; CEB). We are going to take some serious hits in this life. That is when we will be faced with the noble call to endure. Beginning in the late 1700’s and continuing into the 1800’s, the United States government and her citizens began a series of forced “removals,” or permanent relocation of Native Americans from the southern states to what was then Indian Territory, the other half of Oklahoma Territory before Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907. In May, 1838, federal troops began seizing control of Cherokees and rounded them up and put them in holding pens until they could be transferred to the west. Many Cherokees endured sickness and disease during this period, and some died because the stockades were infected with deadly viruses such as smallpox. President Andrew Jackson (no relation, trust me), whose portrait now hangs morbidly in the Oval Office, was personally responsible for the many Cherokee deaths that occurred following his signing the 1830 Indian Removal Act. “Light a fire under them; they’ll move,” Jackson is reported to have said. The first detachment on what would become “The Trail of Tears” left in June, 1838, during a horrible drought. Cherokees continued to get sick and die due to the uncompromising heat, and the detachments were postponed until cooler weather. The army was ready to move them again in the fall and as fate would have it, the winter of 1838-39 was one of the coldest on record. On October 11, 1838, the Bell Detachment (one of the many to be moved that winter), containing my great, great, great aunt Mary and her family, began the journey to Indian Territory. Of the 660 or so Cherokees in this detachment, 21 died on the way and were buried in hastily-prepared, frozen graves by the sides of the roads. In other detachments, many more deaths occurred. Those who survived, like Mary, were left in the new territory with little or no sustenance, and many later died as a result of the harsh journey. Moreover, documented cases of rape and other forms of maltreatment point to European and colonial attitudes of superiority that persist today. Mary is one of the ancestors who “speaks” to me, especially when I think I can’t go on. Interestingly, it is often related to another person’s struggle to endure that Mary comes alive and walks with me. As a hospital chaplain, when I would be called to a death—especially the death of a child, and I would struggle with what I could possibly say to the family, Mary would sometimes appear, settle my spirit, and remind me that my presence would be enough. To what have you been called to endure? Are you called to be with others as they endure? If you’re like Job, Mary, and the many saints with whom I’ve had the privilege to share sacred space, I know you will persist. You will endure, my friend, because you are called to do no less. To what, or to whom, are you called to honor? As an expression of my Cherokee spirituality, family is just as much a matter of loyalty and compassion as is biology. In addition to the family of origin “blood” relationships, other family members have been honoring of me as well. For example, take my childhood friend, Melissa. Even after decades and a geographical separation of some 3000 miles, Melissa honors our relationship. Sure, we went for many years without contact, but reconnecting with her during the 2000’s made it seem as if she had always been there. I now live in the Pacific Northwest, and whenever I hear Melissa’s North Carolina accent, it warms my heart, and I long for home. See, Melissa is really family. She’s a sister in the Lord, so to speak, and if she doesn’t hear from me for a long time, she checks in. She is thoughtful. She honors our history. What’s more, our respective spouses honor and cherish who we have become since the days of strollers, Play-Doh, baseball gloves, and pom-poms. Many of the memories of our Charlotte childhood are fond ones. My earliest memory of “Missy” is of her blond curls and sweet disposition. I still have a great love for my hometown and my first neighborhood near Windsor Park, and I associate that love with Melissa and those who celebrate our Southern upbringing. We grew up around the corner from each other; that is, until her family moved “down the road apiece,” as we would say in the south. In time, we moved a few miles away as well. Our families kept in touch. My mother, Jean, and Melissa’s mother, Dorothy, played bridge together for decades. I recall many a Monday evening, when it was Mom’s turn to host, the laughter and joy that our mothers shared with friends, even though I was forced to make myself scarce when the women all converged in our living room. I would employ my stealth, however, and patter to the doorway whenever I heard Dorothy speak of the beautiful girl with the blond hair and sparkling eyes that I pretended not to notice. I recall one evening, while in my early teens, going to the Barclay Cafeteria with Mom and Dad and encountering Melissa and, to my great annoyance, her date. That might have been the moment I realized life was utterly unfair! I have a hunch that our mothers would be happy that Melissa and I stay in touch, and that we still hold each other dear. I hope I have honored Melissa with this reflection, as nothing would please me more. When we honor, we reflect goodness. It is a type of goodness that is uplifting for its recipient, or it fails to do the honor intended. Whenever I hear from Melissa, I’m uplifted. It makes me think of Charlotte’s Eastside, where we grew up; of how the years just fly by, and that we are all eventually returning to the earth from whence we came, our spirits abounding within the cosmos. Our reconnection was, in fact, cosmic. Some of the best news in human history was galactic, and it was honoring: “We’ve seen his star in the east, and we’ve come to honor him.” (Matthew 2:2, CEB). Are you called to be uplifting for someone? How will your words or deeds honor them? Thank you (“Wah doh!”) for reading. I am truly honored. Be well, and, when you can, be honoring. |

Yona Ambles"YOH-nuh" (yonv) means "bear" in Cherokee. Thanks for visiting! Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed