|

With The Rev. Dr. Ken Meeks, Jr., Ministry Mentor

I have been fortunate enough to have been on the receiving end of a few good mentoring relationships over the years. Each one, fortunately, has taken me to a new level. The best ones do two things: 1) Celebrate who you are without a concern for core character change; 2) Keep you moving toward your goal. One wonderful mentor was Dr. Kenyon Meeks. Ken was my ministry mentor during seminary, and he had his hands full. I had been severely hurt in one denomination and transitioned to another during our time together. During my second year in seminary, my mother died. She and I were very close, and Ken was there for me. I had become an emotional minefield, and Ken negotiated it with great precision. He was a calm, thoughtful presence as I struggled to deal with the mind-screws that sadly pervade the sometimes sadistic world of professional ministry. The ordained ministry reflects the society it attempts to serve. Like most professions, there are good eggs and bad eggs, and some truly rotten ones. I have personal and professional experience with all three. I will always be grateful for my time with Ken. If you possess the annoying tendency to tilt toward windmills the way I do, by all means do so in style, with someone like Ken watching your back. When we mentor another person, we assume a moral responsibility. When Hippocrates said, “Do no harm,” I think he had a lot more in mind than the dispensing of medicine. We are human and we will harm others; we can’t seem to help it. Mentoring others gives us an opportunity to not only assess the mentee but to assess ourselves as well. No real guidance of the other takes place without that self-assessment. Are you being called to mentor or help guide someone to a new level of being? How do you know if it’s a good fit? You answer the call. If that person remains on the line, stay connected. If the connection isn’t lost over time, it’s probably a good fit. I hope 2018 brings you into a positive mentoring relationship in one fashion or another. Perhaps you are due for the goodwill and skill that only a certain person can offer you; and maybe, just maybe, someone deserves your expertise and kindness. Happy New Year!

1 Comment

I was expected to go nowhere. They said I was lazy, unmotivated. When it came to math, teacher remarks went something like this: “Bryan just won’t apply himself. He won’t sit still, and he disrupts my class with his showing off and silliness.” They seemed convinced that I was out to get them.

Such comments usually came from uninformed teachers who couldn’t comprehend how I, at age 12 for example, could converse about Watergate or memorize the pages from Peter Benchley’s Jaws or Irwin Shaw’s Rich Man, Poor Man, but was locked in a perpetual struggle with fractions and sleepy from the same old stale colonial American “history.” The truth is, I was confoundedly bored, but legitimately challenged, and I didn’t fare well with the then-pathetic North Carolina school curriculum, which consistently ranked low at the national level. By age 14, I was shut down, and stayed that way until I dropped out of high school. One high school “guidance counselor” asked me about my future plans. I told him what I wanted to do. He stared at me from behind his Mr. Peabody glasses and said, “Well, those guys are smart.” I became convinced, though, that the many teachers and so-called guidance counselors were wrong about me, and returned for my GED. The rest, as they say, is history; my history. Regarding the math, I had what is now known as “dyscalculia,” a genuine disability with respect to mathematics. My father, God rest his soul, could not or would not wrap his mind around the idea that his only son was a failure at math. My mother wasn’t any good at it, either, so she would ask Dad to “help” me. I struggled to comprehend, and he would sigh. Then he would yell. Then he would scream. Not a pleasant time in my life. This was a man with a recorded IQ of 180 and had received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. He turned that down after being promised that he would enter flight school for the U.S. Navy after just two years of college, and he was never the same after that broken promise, having lost two rare opportunities. He had difficulty, I think, embracing much of his own personal history, a family history that included forced Indian removal and further shattered U.S. government promises having to do with roads never built and monies never delivered, and a chaotic childhood where he was passed around from person to person. So that’s life in the trenches, I suppose. For the rest of my life I struggled with the numbers, but as a canine behaviorist I could do things with a German Shepherd puppy that awed my clients. This was probably because the dogs spoke to me in ways that the naysayers and the math formulas could not. The years past and Dad mellowed a bit, and I recall his pride when I graduated college and later, seminary. The figurine in the photograph of the old man and the butterfly was a present from my father later in life. He said it reminded him of my gift with the dogs. During those later years, Dad and I became friends, and it was then that it became possible to embrace my past. The figurine reminds me regularly of a man who loved me as best he could considering the circumstances he was dealt. How about you? Is it possible that you’re being called to embrace something from your past? If so, drop me a line. I would love to hear about it. With PGA professional and human being extraordinaire, James Black, in my hometown of Charlotte, N.C., 2017.

When I was a teen, my golf coach, James Black, used to say, “Muscle memory, young man, muscle memory,” as he stood in front of me and held my head still while I learned the art of the swing. He was and is a kind soul. I had a nice swing, but he knew that I didn’t have the tools to be a great golfer. He was more interested in my spirit. Like me, Mr. Black, as I still like to call him, is a Charlotte, N.C. native. These days, instead of encouraging me in my golf swing, he tells me that I’m “precious.” As one of the first African-American golfers to earn a Professional Golf Association (PGA) tour card, he has much to be bitter about because black golfers in those days endured unspeakable discrimination and abuse from white golfers who had half the talent of golfers like James. Yet, Mr. Black isn’t bitter. He tells me, “I love you and there ain’t a thing you can do about it.” Mr. Black is called to encourage, and he still emboldens me some 39 years later. Sometimes, encouragement is a matter of just a few words … or none at all. Perhaps someone recently gave you a “thumbs up,” either in person or on social media. My Little League coach, Mr. Woodard, used to yell, “Chunk that rock!” as I stood on the pitcher’s mound and ripped them past the batters, one by one. So many persons have made a difference for me at key points in my life. My middle school English teacher, Miss Stenhouse, thought I was a good writer. She had the thick, voluptuous lips that women would kill for, chestnut hair that danced on her delicate shoulders, and awesome brown eyes. She was 21, and I was 14. I was already spellbound, but when she gave me an “A” on my writing essay and complimented me, I was done for. My heart still skips a beat when I remember. Who needs your encouragement? Keep in mind the difference between advice and encouragement. One imparts specific information, solicited or unsolicited. The other is a warm summer breeze that blows across your bow as you attempt forward movement. It is superior to advice in so many ways, not the least of which is spiritual. When we encourage, we begin the wonderful process of positive endorphin release in the other person’s brain, something that can trigger new beginnings. Don’t be shy. Your encouragement may very well carry someone a long, long way. Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays! The Rev. Joseph A. Wiggins, Methodist minister and cavalry chaplain

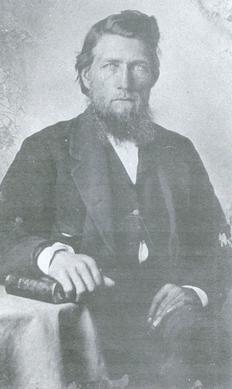

This particular post is specific to those called to the ordained ministry and those who love them. This is a calling that has come to the young, to the old, and those in between. Attempting to describe it seems pointless since, after almost 25 years, my words cannot do it justice. Depending on one’s denomination within the Christian tradition (as that is the tradition to which I can speak), it can involve many things: preaching, pastoral care, administering of sacraments or ordinances, teaching, counseling (something many clergy need to steer clear of, for everyone’s sake), management of budgets, and more. If you are called to the ordained ministry, I want to encourage you. I encourage you because the party line by higher-ups is often that of discouragement. If God is in fact the One Who called you, then God likely knows what God is doing and the Spirit’s opinion trumps those of your detractors. What’s that you say? You don’t think you have any detractors? Trust me, you will. See, one of the many mysteries of this subsection of the greater world is that the emotional, psychological, spiritual, and sometimes physical toll is and always has been high for those ordained to the ministry. If you don’t tick someone off from time to time during the course of your ministry, you are doing something wrong. The stress can be tremendous. Despite this, I cannot think of anything more important than sharing the sacred space of God's love with others. My 2nd great-grandfather, Rev. Joseph A. Wiggins, was a circuit-riding Methodist minister and cavalry chaplain. According to his obituary (seriously!), he annoyed a great many in his efforts to promulgate the Gospel. Now, I’m sure Grandpa Joe and I are (I have a perpetual relationship with my ancestors, so I use the present tense to mark our relationship) at odds in our respective theologies, but regardless of where one rests on the theological spectrum, giving so much of self for others can be brutal work. Yet, most who have been in it for any length of time would tell you it has been worth it. The call to be “Separate Yet Equal” is sometimes described as being “set apart for the specific work of the ministry.” The comprehension of it by the clergyperson’s constituency varies. In some denominational life and thought, holy orders can represent a very separate and, unfortunately, unequal existence for the ordained. This is usually marked by an ordination service where a bishop, representing a direct line of bishops going back to Jesus Christ, lays hands on the candidate. In others, the service is considered a special service, yes, but no special authority (such as intercessor between God and the people) is conveyed upon the candidate for his or her role except that of preacher, caregiver, and one who administers the ordinances or sacraments. Of course, in most Protestant denominations, expectations of what the ordained ministry is varies from congregant to congregant, and therein lies much of the conflict that takes place in the ministry. If you are called in this sense, I won’t try to talk you out of it, simply because it is not my place (nor anyone else’s) to do so. I will suggest, however, that you keep your eyes open, for as Sheriff Andy said to his son, Opie, “Then if ya have any trouble closing them, why, your opponent will close ‘em for ya.” Do people really want to be helped? I have wrestled with that question for many years. Do people wish to be helped as a whole, I still don’t know. You will encounter the occasional individual, though, that does want help, and it is for him or her that you will be ordained, and it will have been worth every hoop you will invariably have to jump through. God bless you. Restoration and service go hand-in-hand, in that the best service is restorative. Former Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Wilma Mankiller (1945-2010), a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, led a life of restorative service. She even once said, “I want to be remembered as the person who helped us restore faith in ourselves.” During her different phases in Cherokee Nation government—including her tenure as Principal Chief—she implemented restorative benefits. She helped improve infrastructure by providing the Bell, Oklahoma community with running water; reformed and boosted tribal negotiations, and created the Cherokee Nation Community Development Center. Mankiller achieved these things and much more, all while battling sexism, racism, and serious health challenges.

At least a flicker of renewal resides in all of us. Certainly, with most of us, the willingness to employ it rises from the ashes of the many deaths we die as we make our way through adulthood. Our ability to renew and restore is an outgrowth of our intent to do so. If our hearts are not in the right place, no amount of talent will produce the kind of healing that makes us better people. We are, as were our ancestors, called to restore. If we (and they) were not, I would not be writing this, and you would not be here to read it. Restoration may not be a primary calling for you, but it could very well be an auxiliary one. What will you help restore in 2018? Let the world be part of your renewal. Someone, I promise, will benefit. Wah-doh (thank you) for your service. This article first appeared in the December 2017 issue of Talking Leaves, the newsletter of the Mt. Hood Cherokees.

How should we define what it means to be Cherokee in the 21st century? Enrolled members of the Cherokee Nation, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and the United Ketoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma represent a clear standard for Cherokees. Some view non-citizen descendants as “wannabes” regardless of the individual’s heritage, knowledge, or community involvement. Despite this, there seem to be three things that identify one as Cherokee. They involve the congenital or ancestral, the cultural or societal, and the metaphysical or spiritual. Congenital/ancestral (It’s not about the cheekbones) During the 2012 election cycle, Elizabeth Warren, a United States Senator from Massachusetts for the Democratic Party, said that a family member told her that Warren’s “papaw” (grandfather) had high cheek bones and, therefore, was an Indian. The cheekbone declaration and lack of curiosity coming from this woman regarding Cherokee culture and history are breathtaking. When pressed, Warren was unable to support her assertions of being Cherokee. To date, Warren has never sufficiently addressed those early assertions regarding Cherokee descent to satisfy this writer. She has preferred to remain silent, showing no interest in learning more about our history, culture, or concerns. In the more recent election, Donald Trump called Warren “Pocahontas,” which generated laughter and further sarcasm among more than a few Americans. Again this week, Trump, with a portrait of Andrew Jackson looming in the background, referenced Pocahontas (meant to insult Warren) while attending a Navajo Code Talker ceremony in the Oval Office designed to honor these veterans for their service. Such comments demonstrate the profound ignorance and stereotypes about indigenous life and heritage. Pocahontas was a Powhatan and endured kidnapping, rape, and an early death; nothing funny about that. As Cherokees—enrolled or not—we must speak out against the irrelevance of high cheekbones and the cruel and dangerous conventions of our people. Those of us not endowed with tribal citizenship get caught in the middle of a rather nasty, race-baited quagmire. We’re stuck somewhere between the fumblers like Warren and enrolled Cherokees who were diligently raised as such. Individual Native American self-determination upsets the balance of things within the tribe, even when such self-identification is accurate. I comprehend that Cherokees want to emphasize the nation-to-nation relationship with the United States government, even though Cherokees were Cherokee before such a relationship existed, yet that speaks to my point: One either has Cherokee ancestors or one does not. My dilemma here is the proclamation sometimes put forth that only citizenship and/or race determine who is a Cherokee. More dialogue is in order. Cultural/societal (“the proudest little possession”) An artist named Jimmie Durham has been the subject of recent controversy, particularly amongst Cherokees. The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-644) was instituted to protect tribal members and certified Indian artisans from fraudulent individuals claiming Indian heritage. In earlier times, Durham claimed Cherokee heritage and to date has presented no documentation of Cherokee ancestry. One recent article describes Durham as a “77-year-old white guy.”i Durham should be protested and perhaps disciplined, but my concern lies with the language among some who use race as a primary argument. Fortunately, Cherokee Nation citizens that I know (most of who are of mixed racial origin) are more concerned about Durham’s misrepresentation than his racial makeup. Humorist Will Rogers (my third cousin, three times removed) was a “white guy.” He was also Native American, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. Rogers is reported to have said, “I am a Cherokee and it’s the proudest little possession I ever hope to have.” Today, plenty of others, even in high-level tribal government roles, are white guys. They are also Native American. Clearly, it’s about more than pigmentation. It has been said that of all creatures, the U.S government registers three according to some type of pedigree database: dogs, horses, and Native Americans. If race describes physical features and ethnicity refers to cultural characteristics, how are we to differentiate and bring clarity to this outdated and patrimonial construct? I have at least one “mixed-blood” Cherokee ancestor listed as white on some census roles and Indian or Native American on others. This was a period in history when it wasn’t “cool” to be Native American. Race played a much greater role before and during early European contact, when Cherokee mixed marriages were few. Is our current condition about race, or is it about how each Cherokee expresses and celebrates his or her identity and heritage? Regarding Jimmie Durham, the purposeful distortion of his identity supersedes his skin color. He was wrong in principle, regardless of his race. Being Cherokee is certainly about birthright but it’s also about being part of a sacred community that in contemporary times represents people of mostly mixed-racial heritage and a sincere, ethnocentric focus on the traditions and values of our ancestors. Metaphysical/spiritual (“All my relations”) The spiritual aspect of being Cherokee belongs to all of us. It lends to more than speculation about cheekbones or DNA sampling, which is spurious at best regarding Native American identity. It’s about deep-seated relationships, such as with one’s higher purpose, others (people, especially ancestors; the created order as a whole—“all my relations”), and self. Many Cherokees have a deep connection with something greater than themselves. Incidentally, one of my second great-aunts was named Julia Pocahontas Lowe. Perhaps Julia’s mother, Cynthia, meant to honor Pocahontas as an expression of her own metaphysical leanings. Most Cherokees with which I am familiar tend to express some sense of reality about something that is beyond their perception and tend to use their awareness to add to the greater good, usually in service to others. How are we to continue to think about being Cherokee? Perhaps stepping back and viewing things from a broader perspective is in order. In December 1971, Canadian Pierre Berton interviewed martial artist and actor Bruce Lee for The Pierre Berton Show. When Berton asked Lee if he considered himself Chinese or North American, Lee, a philosophy major and enjoying the height of his popularity, said that he preferred to think of himself as a human being and that “Under the sky, under the heaven, there is but one family.”ii In times of such division, wise words to ponder. Being Cherokee by citizenship or descent is a distinction, a specific branch of the larger family tree. We possess those qualities that differentiate us from others, while simultaneously demonstrating characteristics that permit us to harmonize with them. Let us continue to relate to the rest of the family with common sense and charity. Bryan Jackson is a member of the Mt. Hood Cherokees. His ancestors span the censuses from the Reservation Roll of 1817 to the 1909 Guion Miller Roll. A few of those ancestors travelled the Trail of Tears in the Bell Detachment. He holds life placement in the First Families of the Cherokee Nation (Sonicooie) and the First Families of the Twin Territories. Sources:

Have you ever encountered one of those “moments”? Have you ever been fortunate enough to be a part of something that led you to believe that you might have a future doing it? Something where you were a standout? I subscribe to the notion that all of us are genius at something by the time we’re 10 years old. Some folks have multiple talents or gifts that they enjoy sharing with others. The dispensing of those gifts is their response. Responding to a calling is an act of courage. It is like walking to the edge of a long diving board for the first time and knowing that the deep end is just that—deep. You might be afraid of the water; of slipping and losing your balance before you even hit the water. What might be preventing you from responding to a calling? Drowning? The wonderful thing about the angels around us is that most of them know CPR, so fear not. Trusting in others is part of a healthy response to a call. Go on—show me your swan dive! When we’re truly called to something, it is our option not to respond. We just might not have the resources in the moment to answer. The universe understands. Don’t be surprised, though, when the invitation returns somewhat aggressively, kind of like all those letters from Hogwarts School that overtake Harry Potter and marks the beginning of his destiny. If you feel ready, grab those reigns. I and others eagerly await your response. Sunset at Seabrook, Pacific Beach, Washington What are you called to discern about yourself? If you’re like me, it’s all a work in progress and the minute you think you might be close to figuring out some things, you’re down for the count again. Self-improvement courses, education, therapy, even—God forbid, some type of clinical training designed to make one more aware of self and others, are available. Thing is, no matter how much of this we do, the calling to awareness is a consistent exercise that we must do if we are to grow. People will be unhappy with us as we push toward our calling. They will despise us, in fact, but character is not defined by our perceived reputations. It is defined by our adherence to our principles. What are the things that do define you? Is there something that establishes who you are and gives you the drive and compassion for what you do? If you are not who you thought you would be, then who are you, and how can you love yourself regardless? Hey, maybe you’re better than you thought you’d be! Go get ‘em, Tiger! If that is indeed the case, please remember those of us who didn’t turn out quite as well as we thought we might. Have mercy; be aware. Our character and our propensity to offer grace to others can lead us to a higher level of awareness. Our consciousness, our mindfulness, our understanding and appreciation of ourselves and others, these are the qualities that lead to a higher awareness that enable us to be what we are called to be, and do what we are called to do.  I realize that a lot of people go through life without ever considering what they might be called to do. It’s not something that is part of their reality. Yet, it could be. Take, for example, the young lady in this photo. She was called yet again to marriage, as was I, and the greatest win of my life was the day she said “I will.” We've been married over 20 years, and I look forward to the next 20. She was further called to excellence as an Education for Ministry mentor, Catechesis of the Good Shepherd catechist, and sustainable investment professional, among other things. Her "being" is just as important to her as her "doing." Calling sometimes implies religious or spiritual beliefs. “What am I here for?” or “What is God/The Great Spirit asking me to do?” are the kinds of questions that Christians like me sometimes grapple with. Those who profess no particular belief in a higher power have demonstrated that they, too, wrestle with the notion of calling. These are materialistic times. We are materialistic people, even though we prefer not to think about that. At some point, we must settle for ourselves why we are here, and most importantly, who we are going to help while we’re here. This gets us to the deeper questions and will carry us to the calmer end of the pool where our money and our stuff, or lack of it, no longer suck us to the bottom. I invite others, both here and in an upcoming book, to investigate their respective calling(s) and how identifying, naming, and realizing those callings can change lives in the sacred circle of people with whom we share those lives. Caution: Living out a calling usually entails risk, great risk. Sometimes, that risk involves the loss of significant relationships. It will, however, bless your being with new relationships that take you where you need to be. Let’s take the mystery as it comes, and while we’re at it, help one another to embrace our calling, be it our first, our 20th, or our last. We are called to do and be no less. To what are you called to be in 2018? Shalom, Peace, di-da-yo-li-hv-dv-ga-le-ni-s-gv (until we meet again). Bryan |

Yona Ambles"YOH-nuh" (yonv) means "bear" in Cherokee. Thanks for visiting! Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed